Estefania Cassingena Navone

and Other File Handling Functions Explained" width="1505" height="788" />

and Other File Handling Functions Explained" width="1505" height="788" />

Hi! If you want to learn how to work with files in Python, then this article is for you. Working with files is an important skill that every Python developer should learn, so let's get started.

In this article, you will learn:

Let's begin! ✨

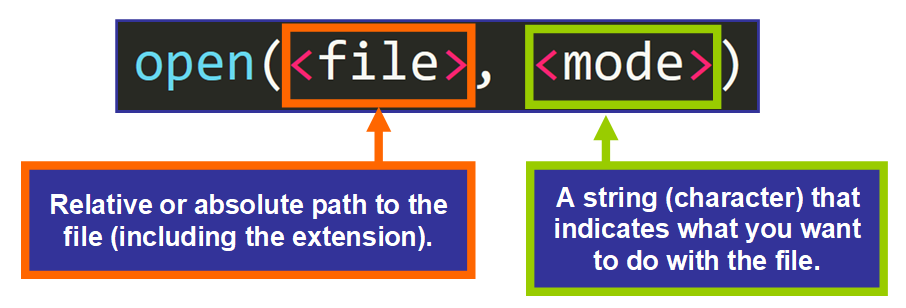

One of the most important functions that you will need to use as you work with files in Python is **open()** , a built-in function that opens a file and allows your program to use it and work with it.

This is the basic syntax:

💡 Tip: These are the two most commonly used arguments to call this function. There are six additional optional arguments. To learn more about them, please read this article in the documentation.

The first parameter of the open() function is **file** , the absolute or relative path to the file that you are trying to work with.

We usually use a relative path, which indicates where the file is located relative to the location of the script (Python file) that is calling the open() function.

For example, the path in this function call:

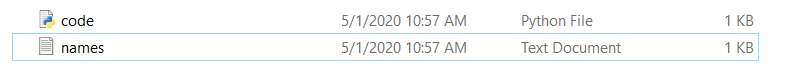

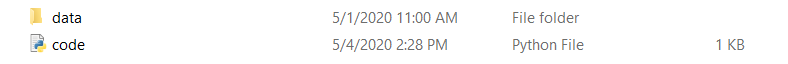

open("names.txt") # The relative path is "names.txt" Only contains the name of the file. This can be used when the file that you are trying to open is in the same directory or folder as the Python script, like this:

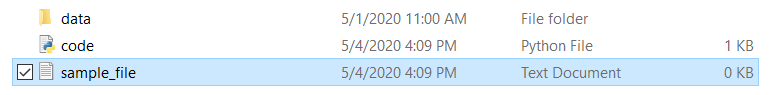

But if the file is within a nested folder, like this:

The names.txt file is in the "data" folder

Then we need to use a specific path to tell the function that the file is within another folder.

In this example, this would be the path:

open("data/names.txt") Notice that we are writing data/ first (the name of the folder followed by a / ) and then names.txt (the name of the file with the extension).

💡 Tip: The three letters .txt that follow the dot in names.txt is the "extension" of the file, or its type. In this case, .txt indicates that it's a text file.

The second parameter of the open() function is the **mode** , a string with one character. That single character basically tells Python what you are planning to do with the file in your program.

Modes available are:

You can also choose to open the file in:

To use text or binary mode, you would need to add these characters to the main mode. For example: "wb" means writing in binary mode.

💡 Tip: The default modes are read ( "r" ) and text ( "t" ), which means "open for reading text" ( "rt" ), so you don't need to specify them in open() if you want to use them because they are assigned by default. You can simply write open() .

Why Modes?

It really makes sense for Python to grant only certain permissions based what you are planning to do with the file, right? Why should Python allow your program to do more than necessary? This is basically why modes exist.

Think about it — allowing a program to do more than necessary can problematic. For example, if you only need to read the content of a file, it can be dangerous to allow your program to modify it unexpectedly, which could potentially introduce bugs.

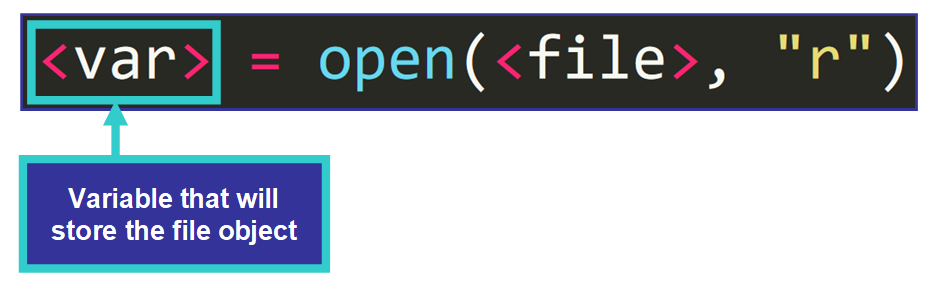

Now that you know more about the arguments that the **open()** function takes, let's see how you can open a file and store it in a variable to use it in your program.

This is the basic syntax:

We are simply assigning the value returned to a variable. For example:

names_file = open("data/names.txt", "r") I know you might be asking: what type of value is returned by **open()** ?

Well, a file object.

Let's talk a little bit about them.

According to the Python Documentation, a file object is:

An object exposing a file-oriented API (with methods such as read() or write()) to an underlying resource.

This is basically telling us that a file object is an object that lets us work and interact with existing files in our Python program.

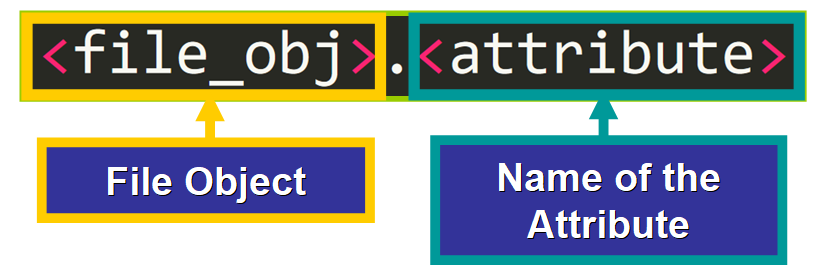

File objects have attributes, such as:

f = open("data/names.txt", "a") print(f.mode) # Output: "a" Now let's see how you can access the content of a file through a file object.

For us to be able to work file objects, we need to have a way to "interact" with them in our program and that is exactly what methods do. Let's see some of them.

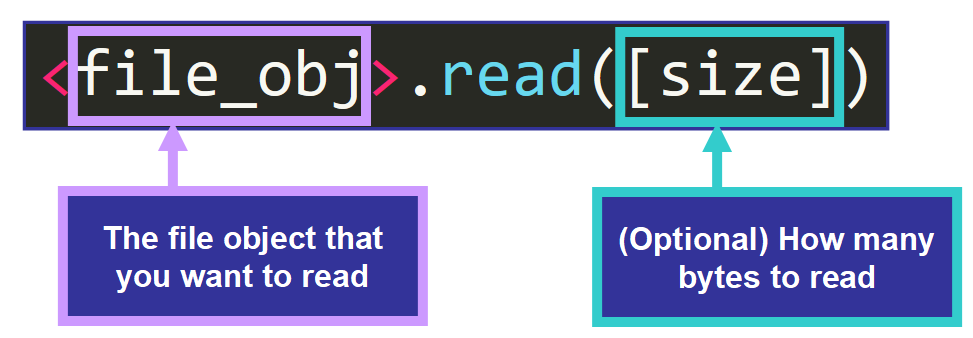

The first method that you need to learn about is read() , which returns the entire content of the file as a string.

Here we have an example:

f = open("data/names.txt") print(f.read()) Nora Gino Timmy William You can use the type() function to confirm that the value returned by f.read() is a string:

print(type(f.read())) # Output

Yes, it's a string!

In this case, the entire file was printed because we did not specify a maximum number of bytes, but we can do this as well.

Here we have an example:

f = open("data/names.txt") print(f.read(3)) The value returned is limited to this number of bytes:

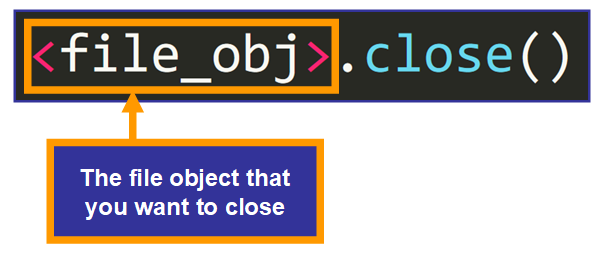

❗️Important: You need to close a file after the task has been completed to free the resources associated to the file. To do this, you need to call the close() method, like this:

You can read a file line by line with these two methods. They are slightly different, so let's see them in detail.

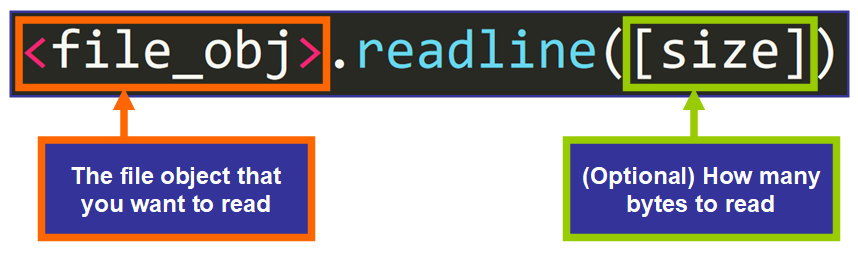

**readline()** reads one line of the file until it reaches the end of that line. A trailing newline character ( \n ) is kept in the string.

💡 Tip: Optionally, you can pass the size, the maximum number of characters that you want to include in the resulting string.

f = open("data/names.txt") print(f.readline()) f.close() Nora This is the first line of the file.

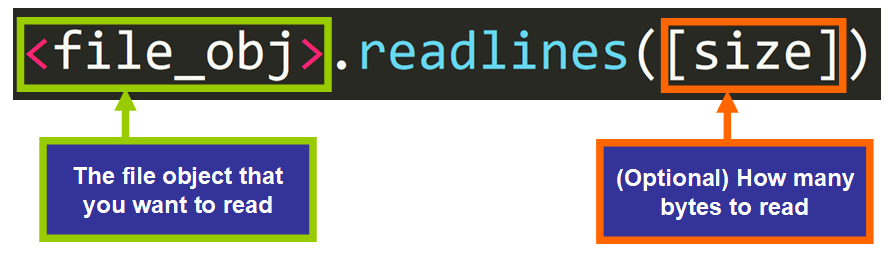

In contrast, **readlines()** returns a list with all the lines of the file as individual elements (strings). This is the syntax:

f = open("data/names.txt") print(f.readlines()) f.close() ['Nora\n', 'Gino\n', 'Timmy\n', 'William'] Notice that there is a \n (newline character) at the end of each string, except the last one.

💡 Tip: You can get the same list with list(f) .

You can work with this list in your program by assigning it to a variable or using it in a loop:

f = open("data/names.txt") for line in f.readlines(): # Do something with each line f.close() We can also iterate over f directly (the file object) in a loop:

f = open("data/names.txt", "r") for line in f: # Do something with each line f.close() Those are the main methods used to read file objects. Now let's see how you can create files.

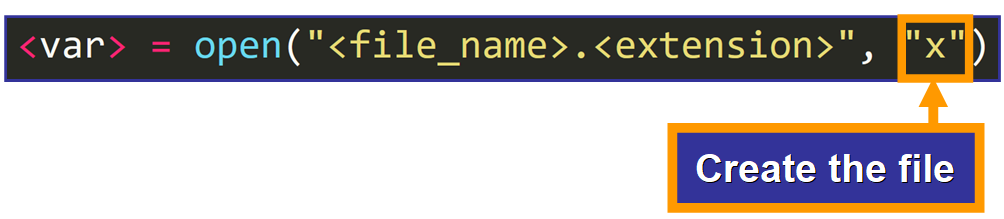

If you need to create a file "dynamically" using Python, you can do it with the "x" mode.

Let's see how. This is the basic syntax:

Here's an example. This is my current working directory:

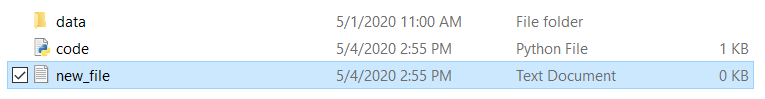

If I run this line of code:

f = open("new_file.txt", "x") A new file with that name is created:

With this mode, you can create a file and then write to it dynamically using methods that you will learn in just a few moments.

💡 Tip: The file will be initially empty until you modify it.

A curious thing is that if you try to run this line again and a file with that name already exists, you will see this error:

Traceback (most recent call last): File "", line 8, in f = open("new_file.txt", "x") FileExistsError: [Errno 17] File exists: 'new_file.txt' According to the Python Documentation, this exception (runtime error) is:

Raised when trying to create a file or directory which already exists.

Now that you know how to create a file, let's see how you can modify it.

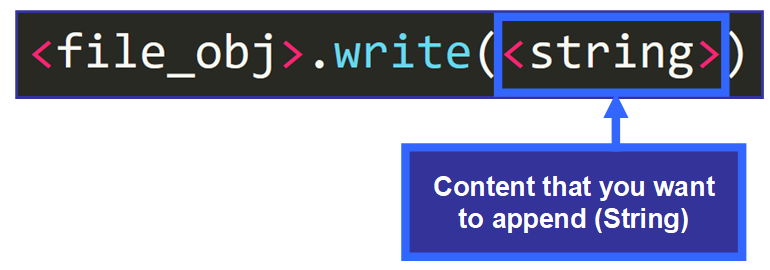

To modify (write to) a file, you need to use the **write()** method. You have two ways to do it (append or write) based on the mode that you choose to open it with. Let's see them in detail.

"Appending" means adding something to the end of another thing. The "a" mode allows you to open a file to append some content to it.

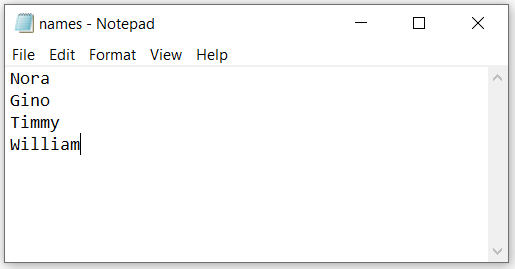

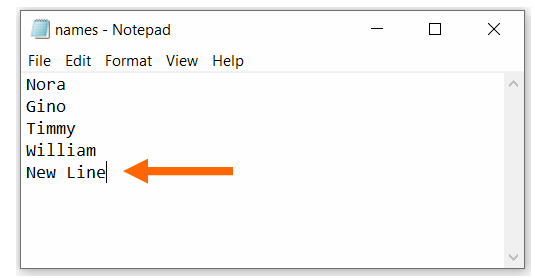

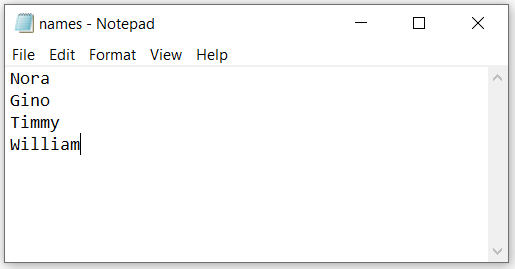

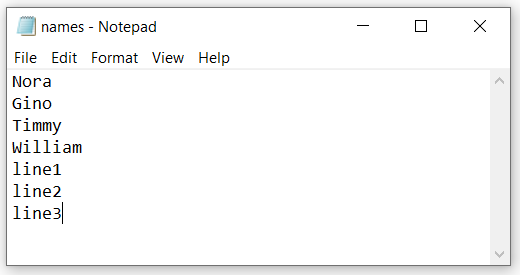

For example, if we have this file:

And we want to add a new line to it, we can open it using the **"a"** mode (append) and then, call the **write()** method, passing the content that we want to append as argument.

This is the basic syntax to call the **write()** method:

Here's an example:

f = open("data/names.txt", "a") f.write("\nNew Line") f.close() 💡 Tip: Notice that I'm adding \n before the line to indicate that I want the new line to appear as a separate line, not as a continuation of the existing line.

This is the file now, after running the script:

💡 Tip: The new line might not be displayed in the file until **f.close()** runs.

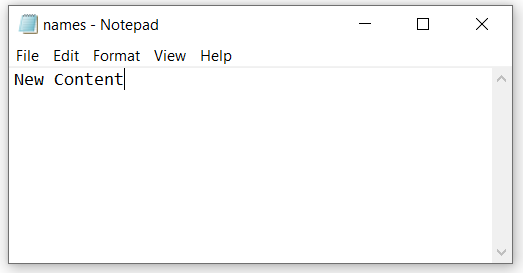

Sometimes, you may want to delete the content of a file and replace it entirely with new content. You can do this with the **write()** method if you open the file with the **"w"** mode.

Here we have this text file:

If I run this script:

f = open("data/names.txt", "w") f.write("New Content") f.close() This is the result:

As you can see, opening a file with the **"w"** mode and then writing to it replaces the existing content.

💡 Tip: The write() method returns the number of characters written.

If you want to write several lines at once, you can use the **writelines()** method, which takes a list of strings. Each string represents a line to be added to the file.

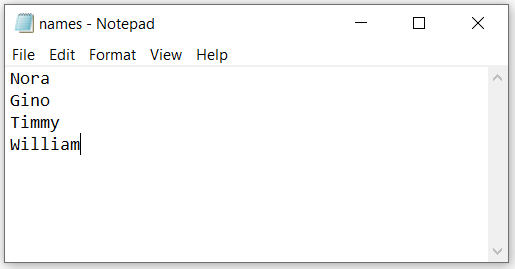

Here's an example. This is the initial file:

If we run this script:

f = open("data/names.txt", "a") f.writelines(["\nline1", "\nline2", "\nline3"]) f.close() The lines are added to the end of the file:

Now you know how to create, read, and write to a file, but what if you want to do more than one thing in the same program? Let's see what happens if we try to do this with the modes that you have learned so far:

If you open a file in "r" mode (read), and then try to write to it:

f = open("data/names.txt") f.write("New Content") # Trying to write f.close() You will get this error:

Traceback (most recent call last): File "", line 9, in f.write("New Content") io.UnsupportedOperation: not writable Similarly, if you open a file in "w" mode (write), and then try to read it:

f = open("data/names.txt", "w") print(f.readlines()) # Trying to read f.write("New Content") f.close() You will see this error:

Traceback (most recent call last): File "", line 14, in print(f.readlines()) io.UnsupportedOperation: not readable The same will occur with the "a" (append) mode.

How can we solve this? To be able to read a file and perform another operation in the same program, you need to add the "+" symbol to the mode, like this:

f = open("data/names.txt", "w+") # Read + Write f = open("data/names.txt", "a+") # Read + Append f = open("data/names.txt", "r+") # Read + Write Very useful, right? This is probably what you will use in your programs, but be sure to include only the modes that you need to avoid potential bugs.

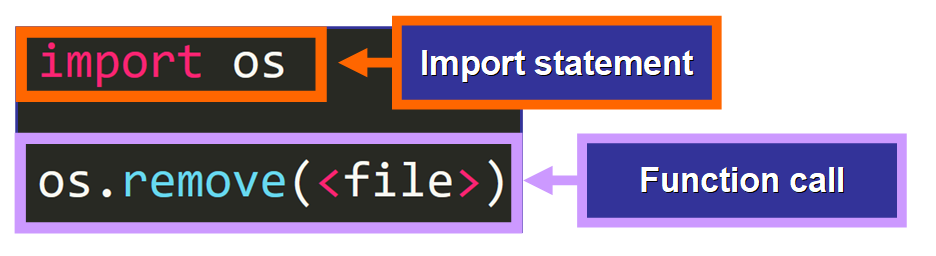

Sometimes files are no longer needed. Let's see how you can delete files using Python.

To remove a file using Python, you need to import a module called **os** which contains functions that interact with your operating system.

💡 Tip: A module is a Python file with related variables, functions, and classes.

Particularly, you need the **remove()** function. This function takes the path to the file as argument and deletes the file automatically.

Let's see an example. We want to remove the file called sample_file.txt .

To do it, we write this code:

import os os.remove("sample_file.txt") 💡 Tip: you can use an absolute or a relative path.

Now that you know how to delete files, let's see an interesting tool. Context Managers!

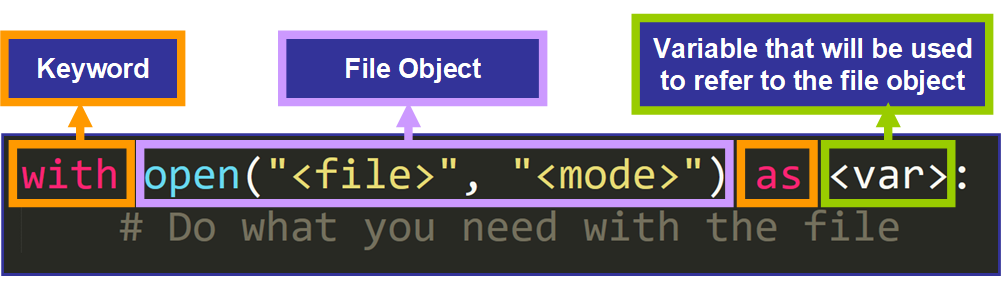

Context Managers are Python constructs that will make your life much easier. By using them, you don't need to remember to close a file at the end of your program and you have access to the file in the particular part of the program that you choose.

This is an example of a context manager used to work with files:

💡 Tip: The body of the context manager has to be indented, just like we indent loops, functions, and classes. If the code is not indented, it will not be considered part of the context manager.

When the body of the context manager has been completed, the file closes automatically.

with open("", "") as : # Working with the file. # The file is closed here! Here's an example:

with open("data/names.txt", "r+") as f: print(f.readlines()) This context manager opens the names.txt file for read/write operations and assigns that file object to the variable f . This variable is used in the body of the context manager to refer to the file object.

After the body has been completed, the file is automatically closed, so it can't be read without opening it again. But wait! We have a line that tries to read it again, right here below:

with open("data/names.txt", "r+") as f: print(f.readlines()) print(f.readlines()) # Trying to read the file again, outside of the context manager Let's see what happens:

Traceback (most recent call last): File "", line 21, in print(f.readlines()) ValueError: I/O operation on closed file. This error is thrown because we are trying to read a closed file. Awesome, right? The context manager does all the heavy work for us, it is readable, and concise.

When you're working with files, errors can occur. Sometimes you may not have the necessary permissions to modify or access a file, or a file might not even exist.

As a programmer, you need to foresee these circumstances and handle them in your program to avoid sudden crashes that could definitely affect the user experience.

Let's see some of the most common exceptions (runtime errors) that you might find when you work with files:

According to the Python Documentation, this exception is:

Raised when a file or directory is requested but doesn’t exist.

For example, if the file that you're trying to open doesn't exist in your current working directory:

f = open("names.txt") You will see this error:

Traceback (most recent call last): File "", line 8, in f = open("names.txt") FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'names.txt' Let's break this error down this line by line:

💡 Tip: Python is very descriptive with the error messages, right? This is a huge advantage during the process of debugging.

This is another common exception when working with files. According to the Python Documentation, this exception is:

Raised when trying to run an operation without the adequate access rights - for example filesystem permissions.

This exception is raised when you are trying to read or modify a file that don't have permission to access. If you try to do so, you will see this error:

Traceback (most recent call last): File "", line 8, in f = open("") PermissionError: [Errno 13] Permission denied: 'data' According to the Python Documentation, this exception is:

Raised when a file operation is requested on a directory.

This particular exception is raised when you try to open or work on a directory instead of a file, so be really careful with the path that you pass as argument.

To handle these exceptions, you can use a try/except statement. With this statement, you can "tell" your program what to do in case something unexpected happens.

This is the basic syntax:

try: # Try to run this code except : # If an exception of this type is raised, stop the process and jump to this block Here you can see an example with FileNotFoundError :

try: f = open("names.txt") except FileNotFoundError: print("The file doesn't exist") This basically says:

💡 Tip: You can choose how to handle the situation by writing the appropriate code in the except block. Perhaps you could create a new file if it doesn't exist already.

To close the file automatically after the task (regardless of whether an exception was raised or not in the try block) you can add the finally block.

try: # Try to run this code except : # If this exception is raised, stop the process immediately and jump to this block finally: # Do this after running the code, even if an exception was raised This is an example:

try: f = open("names.txt") except FileNotFoundError: print("The file doesn't exist") finally: f.close() There are many ways to customize the try/except/finally statement and you can even add an else block to run a block of code only if no exceptions were raised in the try block.

💡 Tip: To learn more about exception handling in Python, you may like to read my article: "How to Handle Exceptions in Python: A Detailed Visual Introduction".

I really hope you liked my article and found it helpful. Now you can work with files in your Python projects. Check out my online courses. Follow me on Twitter. ⭐️